A detailed technical description of the site!

A post after a long time. To be honest, a lot of us have been juggling our normal lives and the website work. Hence dedicating time to write a blog post is not always possible. Having said that, lets talk about today’s post.

So this post is all about the architecture of the site and how we have been able to maintain the site with zero financial costs w.r.t the servers et al. This post talks about the way the site operates from data entries to the final visualisation. Before I begin, it’s important to note that we have kept the site free of ads and corporate associations and have still managed to serve millions of site visits all thanks to free platforms like GitHub and Google Sheets. Without these freely available technologies, none of this would’ve been possible or sustainable in the long run.

Lets dive in then!

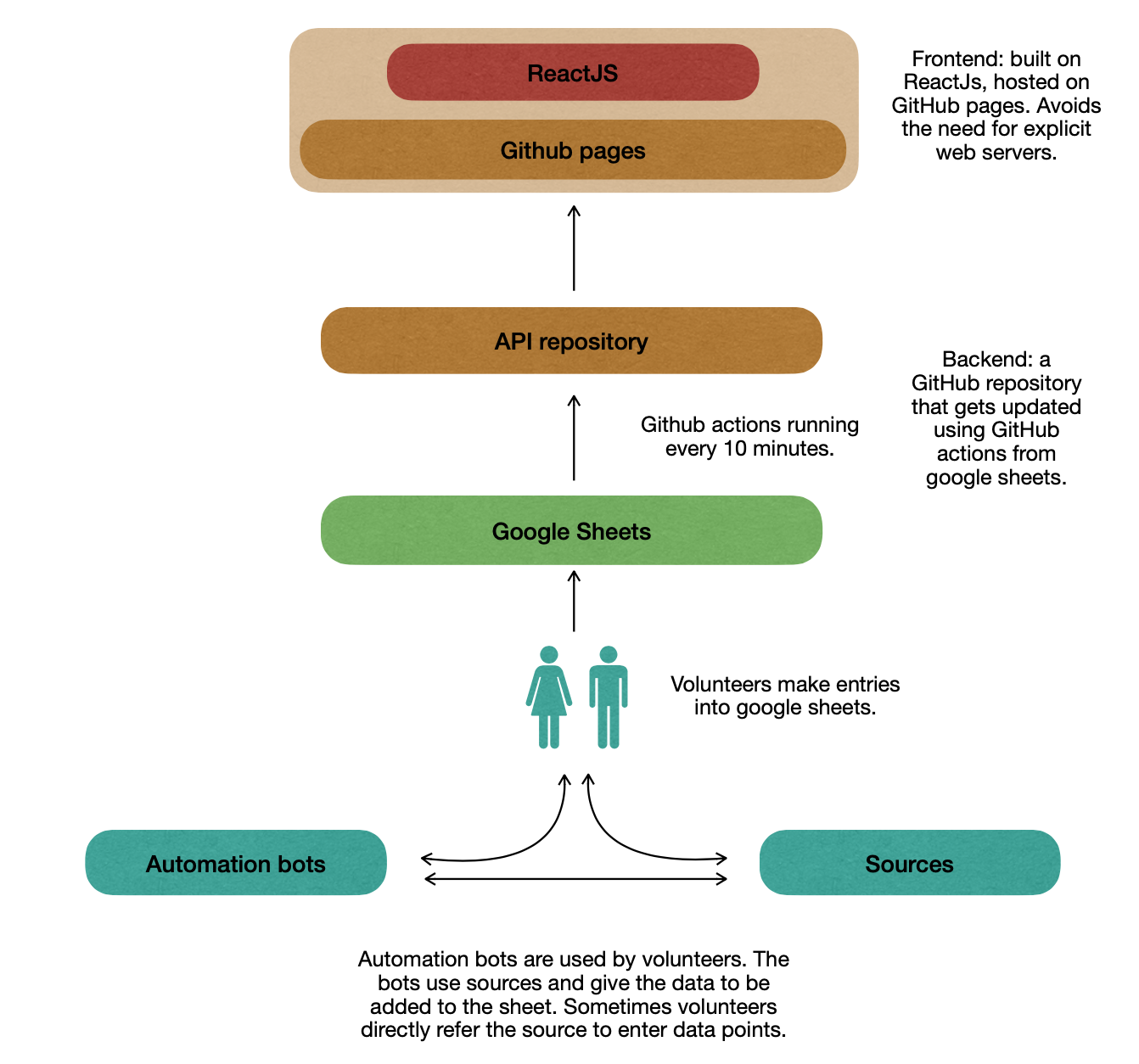

So here’s a diagram that can help you to understand the overall flow:

Before I start, a few naming conventions I’ll use -

Webserver - a server that serves a webpage to a client (browser, mobile et al).

Backend/application server - a server that can take requests on the fly and use business logic to give back data dynamically.

So lets talk about the whole flow. I’ll start from the top and go to the more granular lower layers. At the top is the webpage that you all have come to recognise. This is built on ReactJs. The website is hosted on GitHub pages. GitHub pages can be visualised as a free cloud based platform where one can host their website without worrying about the underlying webservers. This provides a unique advantage in terms of scaling. Had we hosted our site on a privately owned webserver, we would have to account for the cores, memory and iops based on the increased/decreased users visting the site. With GitHub, this is elevated. Now one thing to note here is that the websites hosted are static web pages. That is, the site is just a html page with some javascripts that will get served to the browser. This essentially means that all the data to be shown has to be present in a GitHub repository for the website to work. Fun fact, this blog is also hosted on GitHub pages :)

GitHub pages websites also come with some limitiations on the size of the site and things as such. These can be referred here: GitHub Pages.

Before I move further, the maps that we show on the website are adapted from Guneet’s GitHub repo. There have been some modifications made on the map based on the site requirements. Else, most of these are up to date with the latest district boundaries.

So now, lets talk of the backend server. This is where traditionally the business logic sits. Usually this might have a server like nodejs, apache et al which would take requests and then fetch data from a data source and give back the response. The logic in this layer is used to modify data (validity checks, joins, translations and other operations). This layer might also contain a data server which is usually a database (mysql, oracle, redis and many more). This is how a traditional backend would look. Just having a look at this system tells us that this would mean having a machine(s) where we could start our application server and optionally a database server. Once we enter this realm we get into load balancing, DR (Disaster recovery), HA (High Availability) and other technical requirements that has to be managed either by the owner of the manchine(s) or can be dealt with using AWS, Azure kind of services. Either way, it’s a heavy and possibly costly operation. Hence, not viable for a revenue free volunteer run initiative.

The need for backend server is solved using GitHub pages (cons and cavets to follow). This is our API repository (theoretically, our backend server). Technically, we could’ve kept it as a normal GitHub repository and managed, but that would mean that we wouldn’t be able to publish the page for others as a webpage. This repository holds json files. These json files get used in the javascript code of the website to show data on the web pages.

Now who populates these json files?

Enter GitHub actions! A detailed description of GitHub actions is out of scope of this article. So let me try to simplify it to our usecase and explain what we do.

Every 10 minutes, we invoke an action. This carries out the following set of operations:

- First we fetch data from a set of google sheets.

- Then we prepare json files which correspond to these sheets. Also some other json files that we were historically using in the website.

- Next we read these json files and prepare additional json files which are to be consumed by the website.

- Finally, all these json files get checked-in into the API GitHub pages (csv files follow the same approach).

The above mentioned set of activities are representative of what we do. The exact steps might differ a bit and can be checked here.

All the work of data conversion is done using these actions. A simplistic way of looking at this would be to imagine a backend server coming up every 10 minutes to read data from google sheets and generate some json files. Mind you, all this works only because there are no requirements for dynamic data generation. For example, if there were a request coming from the website that said - get all data between so and so dates and group them by 7 day averages, then all this logic would have to go into the actions part for every conceivable combination of date ranges (which would be unrealistic to achieve and maintain) and these files would’ve to be kept ready. Or, all the data would’ve to be processed in the frontend using JavaScript logic which would mean a very heavy load on the browser to have all the data belonging to those range of dates. Or a viable but limiting third option could be to have a long running task that would listen in on requests and modify data and send it back (not a great option given the free tier limitiations of GitHub actions). Either way, this approach of having no backend comes with its limitations. The approach of no backend is sufficient for us as of now since we do not foresee any dynamic request needs.

In case you are interested in knowing how we sync sheet to github, here’s the code.

The last, yet the most important layer - The humans

This is where majority of the work happens. Volunteers make entries into google sheets that gets synced using the above detailed out process. To aid the volunteers, we’ve developed some automation using Telegram bots. I’ll be soon writing a detailed post on Telegram bots we use. But in brief, these bots use bulletins fed by volunteers or sometimes predefined sources to read bulletins and then generate the data that needs to be added to the sheets. Here too, the request gets served using GitHub actions which invoke python scripts internally to do data operations.

Why we chose not to run ads

As detailed out above, we have zero costs incurred in terms of logistics for running the website. This indeed has come with its own limitations in terms of functionalities. But given the overall features that can be achieved using these free to use technologies, it makes little sense to invest and maintain our own servers or to team up with corporates to get free machines to run the website. This approach we’ve taken helps us to remain independent of any assocations - financial or otherwise. And more than anything, this is a testament to how not-so-difficult it is to keep things open and free if there’s a will to do so.

Until we write again,

Stay safe!

Bee.